Share this Post

My mom and dad always used to get me a box of See’s Candy for Valentine’s Day. Some years, it was the big white variety box. Others, it was the smaller golden box of truffles.

Why did they always select the smaller box for the truffles? Because they are rich. (The truffles, not my parents.) They’re not meant to be eaten by the handful. After awhile, the richness overwhelms you and you have to hurl to get it out of your system.

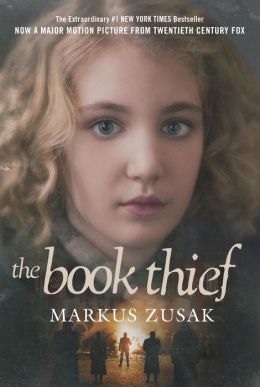

The Book Thief is 550 pages of truffle. It had some delicate, delicious bits. But the longer a reading session I had, the more I felt sick to my consciousness. Like I was going to throw up if I read another page.

The Book Thief had some delicate, delicious bits. But the longer a reading session I had, the more I felt like I was going to throw up if I read another page.

The New York Times reviewer mentioned “…Mr. Zusak’s real but easily oversold charm,” and that’s an apt description.

This is not to impugn the book. It had moments that took my breath away, and more than a few sentences that made me clench my fist in jealousy because I didn’t write them. But overall, I think the hype gave me way too high of an expectation here.

The Language

Some…all right, most…of the motifs were too heavy-handed. Painting over the pages of Mein Kampf so it can become an entirely new book? In terms of make-believe set during the Holocaust, I prefer the film Life Is Beautiful, although it, too, walks a fine line between emotion and treacle.

Some…all right, most…of the language was blowsy and overblown. For starters, this book should have been at least 150 pages shorter. It should have had less of the artsy-for-artsy’s-sake wordplay. The beauty that remained would have felt richer and cleverer. Instead, the language was cloyingly sweet. Reading it felt like stepping on flypaper coated with honey.

Here’s what I’m talking about:

“Somewhere, far down, there was an itch in his heart, but he made it a point not to scratch it. He was afraid of what might come leaking out.”

“…two giant words were struggled with, carried on her shoulder, and dropped as a bungling pair at Ilsa Hermann’s feet”

“As the book quivered in her lap, the secret sat in her mouth. It made itself comfortable. It crossed its legs.”

“Steam was rising weirdly from his clothes.”

“…a new weather report, either of pure blue sky, cardboard clouds, or a sun that had broken through like God sitting down after he’d eaten too much for his dinner”

A boy is described as having “cluttered” breath.

“The horizon was beginning to charcoal.”

“Every night, Liesel would nightmare.”

“…the street that looked like oil-stained pages.”

Remember the truffles? This brings me to my second analogy: Did you know that the average can of soda has so much sugar that the only reason you don’t throw it up instantly is because the phosphoric acid blocks the action of the sugar? World War II is the phosphoric acid. The language is the sugar.

The Characters

Now it’s time to talk characters. I did not like Liesel. Let me rephrase that. I didn’t not like her, either…I just didn’t feel any connection or depth or richness in the character. She was an empty vessel. I won’t remember her because in my mind, she didn’t do anything. I wasn’t convinced that words and books meant that much to her. I didn’t feel that deep connection to the page and the story in her. Her connection was always to other people (Max and Hans, primarily), and books just happened to be the method of expressing that connection. That’s not the same thing at all as loving books and words. There’s a difference.

Liesel floated through the book, buffeted by others in a way that left her with very little agency compared to the others. Hans took in Max. Rosa tried to badger Frau Holtzapfel into coming to the street’s sole basement-turned-bomb-shelter. Rudy tried to become a thief but couldn’t. The mayor’s wife enticed Liesel to become a book thief by leaving her window open all the time. But what did Liesel do? Aside from watch the parade of Jews headed to Dachau, I never felt her as an active presence. It meant I got bored of spending time with her.

I liked Hans and Rosa, but they felt like stock characters. Stock characters with their touching moments, to be sure, but I felt I’d seen their type before. It doesn’t mean Hans isn’t honorable. He is. It doesn’t mean Rosa wasn’t funny. She is. Because now I know what “saumensch” means and can use it in daily conversation. Overall, though, the New York Times guy got it right: the Hubermann household is “colorful to the point of dangerous whimsy.” For me, it stepped right on past that line.

The Narrator

Now, let’s talk Death as the narrator. I like it as a concept. In fact, I’m jealous of it. I think it’s awesome, and it mostly works here. I liked his constant lists and asides. I liked how he spoiled plot points. Holy hell, this is Death. Of course he does unexpected shit. Why do you think life insurance exists? Expecting Death as a narrator to tell a fully linear, traditional story with no spoilers so we habit-bound readers don’t get our panties in a bunch is just stupid.

Expecting Death as a narrator to tell a fully linear, traditional story with no spoilers so we habit-bound readers don’t get our panties in a bunch is just stupid.

Want a book like that? Find one not narrated by the most destructive and unpredictable force humanity has ever known.

I loved it when Death said, “So much good, so much evil. Just add water.” As well as, “For me, the sky was the color of Jews.” To me, that’s evocative writing, the exact opposite of the sugary tripe quoted above. And Death’s final words to Liesel…is there a more perfect way of summing up World War II?

Still, what keeps this device from becoming transcendent for me is the treacle factor. The colors, the souls, the adverbs (oh, God, the adverbs), the colors again…it would be fine in small doses. Through the course of a 550-page book, it’s overkill.

The Verdict

When I think about this book, two storm fronts collide in my head: beauty and treacle. Sugar and phosphoric acid. They fight so hard against each other that they cancel each other out.

I didn’t hate the book. I didn’t even dislike it. I’d give it 3 out of 5 stars. But I didn’t love it. I doubt I’d ever read it again. It’s sentimental in a very dangerous way, a way I was warned about in college, when I wrote sentimental stories that bludgeoned the reader with import! meaning! emotion! artifice!

It’s sentimental in a very dangerous way, a way I was warned about in college, when I wrote sentimental stories that bludgeoned the reader with import! meaning! emotion! artifice!

It’s a dangerous bargain to make as a writer, because the downside is a reaction like mine. I can’t deny that I felt things as I read the book. But most of the things that stick with me have nothing to do with the narrator or the main character, and they probably aren’t what the author intended me to remember.

The Takeaway

Forget books. Forget thieves. Forget Liesel, Hans, and Rosa. Here’s what will stick with me:

- Rudy dressing in blackface as Jesse Owens

- Rudy placing his little sister’s teddy bear on the chest of the dying Allied pilot trapped in his plane

- Michael Holtzapfel, who hung himself after surviving Stalingrad (“hung by a lasso of snow”). Aside: it wasn’t Stalingrad that killed him. It was Germany. I disagree with Death on this one.

Kind of like the book as a whole.

Share this Post

More Scintillating Posts

Fire, Water, Burn: California Is a Bloodhound Gang Song

December 4, 2019How to Translate a Foreign Language Video on YouTube

May 17, 2019

About the Author

I write non-fiction, fiction, and run the YouTube Channel The Girl in the Tiara. My first non-fiction book, The Hunt for Anna Pavlovna’s Stolen Jewels, will be published by Pen and Sword History in 2026. To keep in touch, sign up for my royal history newsletter here.