Share this Post

What made you choose the city or town that you live in? Was it your job? Was it because you grew up there? Was it because you can afford it? Was it because you like the view?

What if you had to start over and pick someplace new? Where would you go? How would you decide where you should be?

That’s the situation I’m in right now, and not entirely by choice.

This is the story of what drove me out of my home state of California.

Home Is Where the Insurance Policy Is

In late 2011, the hubby and I bought a house. It was cheap because America’s economy was still in the shitter and no one else wanted to buy a thirty-year-old house in the country. It had a million-dollar view but zero curb appeal. I didn’t care. We moved to a tiny town no one had heard of and drove twenty minutes one way to the nearest Starbucks. I pounded out a running trail on the property and painted my writing room pink. It seemed like heaven.

But there were already warning signs that something would eventually go very wrong.

Because we were in the country, it took a few tries to get homeowner’s insurance. Several companies turned us down flat. When one finally accepted, they sent an inspector out to look everything over. He glanced at the heavy juniper bushes surrounding the house, flanked by oak and pine trees. “Yeah, you’re good,” he said.

At the time, I believed him.

When It Rains, It Pours

When we first moved in, I thought our biggest problem was going to be the well. Because this is California, we were in the middle of a drought. Also because this is California, that drought lasted for years. The period between late 2011 (exactly when I bought my house) and 2014 was the driest in the state’s history, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. I took two-minute showers and made plans for what to do when I turned on the tap and nothing came out.

Fast-forward to the winter of 2016/2017. It rained. A lot. I washed my hair almost every day, grateful for that slick slide of freshly washed strands.

Fast-forward again to October of 2017, when the Tubbs Fire raged through Santa Rosa, causing roughly $1.3 billion of damage. Why? Because stuff grows fast when it rains. Then it dries into tinder when it heats up. Also because PG&E, but we’ll get to them in a minute.

Fast-forward again to November 8, 2018. The Camp Fire destroyed the town of Paradise, becoming the most expensive natural disaster in the world and the deadliest in the state’s history. 85 people lost their lives. The fire destroyed more than 18,000 structures and caused an estimated $16.5 billion in damage. PG&E’s abysmally maintained equipment sparked the fire that caused all that.

The Asshole Bridge Troll of Doom

Fast-forward a couple weeks later, to December 1, 2018. My homeowner’s insurance renewed for the year, before the true costs of the Paradise fire were widely known. But they sure as hell became widely known, because someone at the insurance company took one look at my zip code and said, “Fuck that place and fuck those people.” I imagine someone using a big red “CANCELLED” stamp and pressing it onto my file as hard as they could.

I have no proof of this, but I imagine this decision was made shortly after the policy renewed, in the wake of the Camp Fire and the no-less-devastating storm of media coverage that followed. But because the law says the insurance company only has to give me 45 days’ notice of the cancellation, I didn’t know about it. The insurance company just sat on that information, like some asshole bridge troll who knows perfectly well all the wooden planks are rotted but keeps its mouth shut as you skip merrily toward your doom.

On January 29, 2019, in the wake of the Camp Fire, PG&E filed for bankruptcy. As of this writing, it’s the largest utility bankruptcy in U.S. history (LA Times). At the time, they were only on the hook for that particular fire. CalFire initially cleared them of starting the Tubbs fire, but later photo evidence may have nailed them on this one, too.

It wouldn’t be the last.

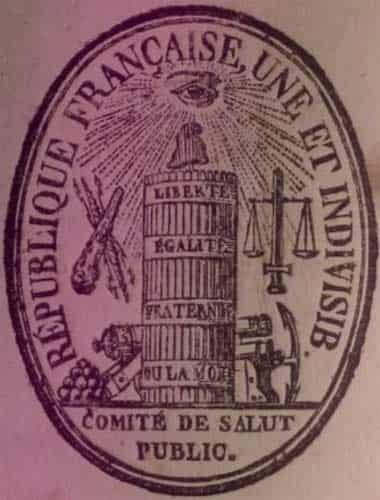

The Committee of Public Safety

Yes, I subtitled this section with a reference to the French Revolution. Make of it what you will.

Fast-forward to September of 2019. Our power company, PG&E, began the now-infamous public safety power shut-offs that blasted us back to pioneer times. Why was this necessary, you ask? It was the only way they could think of to prevent future fires during peak fire conditions. For NorCal, this means October, when the dreaded north wind blows for days at a time.

Losing power is better than people dying.

If that’s the only way PG&E can prevent people losing their lives, by all means, they must do it. Of course, it would have been better if they’d maintained their near-century-old equipment throughout the past few decades, but I can’t rewrite history so this is the solution we’re left with.

And it doesn’t mean I have to like it. Remember, I’m on a well. No power means no water. With no water, home becomes not where the heart is, but wherever one can find a flushable toilet. It’s not elegant, but it’s reality.

Don’t Fear the Reaper – Fear the U.S. Postal Service

Our area escaped the first couple PSPS events in June and September.

We had no such luck in October.

The first time El Dorado County was affected, we fled to my parents’ house, a few hours away. A tank of gas was cheaper than a generator or a hotel, and home-cooked meals were healthier than days of fast food.

The power was off for 3 days.

When we got home, tired and ready to get back to normal, we checked our mail and there it was – the dreaded homeowner’s insurance non-renewal notice. Our insurance would end in six weeks because we were in a wildfire zone with unacceptable risk.

Insurance we had to maintain as a condition of our mortgage.

No insurance, no mortgage.

Suddenly, home wasn’t so sweet.

It was a death trap for any dreams of financial solvency.

Panic Mode

Two frenzied days of phone calls and Googling only turned up horror stories from neighbors and nearby Foothill residents. Lifelong customers of big companies like Allstate and Nationwide had already been cancelled.

Someone on Nextdoor would suggest an insurer.

Someone in the next reply would say they’d just gotten a cancellation notice from them.

Someone else would say the only carriers who were keeping policies were USAA and the Hartford (through AARP), neither of which I’m eligible for.

What are they all so afraid of? This – Paradise after the Camp Fire:

But it got worse. Someone else would describe the requirements they’d been given to get a policy, usually amounting to thousands (or tens of thousands) of dollars in tree work to clear their property. The most onerous requirements seemed to be handed down by companies in the state’s Fair Plan, a last-ditch consortium of insurers mandated to provide coverage by the state.

The Fair Plan’s most dreaded potential requirement? Clear 200 feet of space in every direction around your property. What if your property line cuts off before that 200-foot mark? Too bad. Clear it or you’re non-compliant and won’t get coverage. I didn’t believe it until I Googled it.

And there was another problem. Supposing you could get coverage…what’s to keep that insurer from cancelling you next year? Absolutely nothing.

I started to wonder: is this happening anywhere else?

Turns out, it is.

Screw College, Become an Arborist

One Pew article I found described similar conditions in Colorado.

Well, similar except for a zero in the cost of the required landscaping in order to retain coverage. Bill Trimarco, the Archuleta County coordinator for Wildfire Adapted Partnership, estimated that creating a 150-foot radius around a house usually costs less than $2,500.

I blinked and leaned toward the monitor. Are you shitting me? I thought.

That had been the cost of getting one large Ponderosa pine removed here. ONE. We got a couple quotes for a big pine in the yard ($2,500 – $3,500) and were flabbergasted. And it’s not just that one I’d probably have to whack. My lot had probably a dozen large pines and oaks within a 200-foot radius. 12 x $2,500 = $30,000.

I don’t have $30,000. Do you?

Reality Bites

We’re going to die in this house, we said when we moved in. And we meant it in a good way, because we believed this was the last house we’d ever own.

Until the day we listed it for sale.

I went to talk to a co-worker in the P&C (property and casualty) space to ask if she could help find us a backup policy while we waited for the house to sell. Rebecca found us a temporary policy, quoted for one year with much less coverage, at five times the cost of what we used to pay – an extra $400/month.

I don’t have a spare $400 lying around every month. Do you?

I wondered how long it would be until someone asked about the house’s insurance. But no one did. Not any of the agents, not any of the people who came to look at the house, no one. It made me second-guess myself. Was I freaking out over nothing? Was I the only one worried about any of this?

A week and a half later, PG&E shut the power off again.

It went off Saturday night and came back on Wednesday afternoon. No fires were started in my neck of the woods, but elsewhere, PG&E equipment may have sparked another major fire – the Kincade Fire. At this point, anyone with a brain is forced to say: What the fuck is the point of the shutoff if their equipment still starts fires?

The Turning Point

Okay, so this story has been a bit of a downer so far.

But this is where it takes a turn.

You’ll recall that we put the house up for sale before being forced out by the PG&E power shutoffs. We’d priced it to sell, knowing it needed repairs and potential yard work, not to mention the potential insurance problems.

It worked.

We had 11 offers within a week and accepted an all-cash offer.

A cash buyer has no mortgage and thus no contractual obligation to carry insurance. A cash buyer can self-insure against wildfire danger and only buy other types of coverage, like liability.

We only received one question from our agent: can your insurance carry forward to the new owner? No – that’s the answer regardless of the home’s insurability, because the policy belongs to the person, not the property. We didn’t get any other questions. I would have answered truthfully if I had.

Home Court Disadvantage

As I write this, just about everything I own is in a storage unit.

I have no address.

I have no place to live.

Tonight, I will check into a motel and will stay there for a week. And then I’ll find another. And then I’ll find another, in another state.

Because although I was born and raised here in California, I can’t stay.

I will never have enough money to afford a $500,000+ home. And that’s okay, because most homes in California aren’t worth their eye-popping price tags.

There are lots of other warning signs that California is, to quote Taylor Swift, a nightmare dressed up like a daydream. The infrastructure is crumbling. Housing costs are out of control. The crowds and traffic are overwhelming. The freeways are full of potholes and garbage. Water management is not good. And corporate greed is bleeding this state dry.

Were I a different person, I might stay and fight.

I might have sucked it up and used a home equity loan to pay for tree work. I might have agreed to pay every spare dime to a more expensive insurance policy….and then tried to figure out how to squeeze out enough to make those equity loan payments, too.

But I’m not that person.

I’m just me, and I’m voting with my wallet.

I’m taking my tax dollars elsewhere.

Future Tense

I understand why insurers don’t want to cover people in rural areas. Their job is to make a profit, and they can’t do that when all the houses burn down. Never mind the fact that the house across the street from mine was built in 1849 and is still standing. We’re dealing with climate change, which trumps history.

The hubby thinks there’s some sort of conspiracy to get rid of CalFire. It’s expensive. And I understand why many urban taxpayers would rather fund education projects and affordable housing projects.

At the same time, we have to think about what these desires and outcomes mean.

- Does it mean homeowner’s insurance companies can tell people where they can and cannot live?

- Does it mean people are no longer going to be allowed to live in rural areas unless they can self-insure?

- What does this do to family-owned-and-operated businesses that operate in rural areas, like dairies, wineries, and farms?

- Can homeowner’s insurance companies charge people already in rural areas any rapacious amount they want with no consequences?

- What happens to property values when an uninsurable home must be sold because the owners can no longer afford coverage?

- What happens to a rural economy when property values take a dive?

- Will taxes go up because counties need more fire stations and fire fighters so their residents have a shot in hell of insuring their homes?

I don’t have the answers.

All I know is that I feel incredibly lucky.

I got to live in an amazing place for 8 years.

And I got out before problems I can’t afford destroyed my financial future.

California is going to have to solve these problems without me. I prefer to listen to Bloodhound Gang songs without feeling like they describe my daily life.

P.S. Not sure what all the Bloodhound Gang references are about? Listen to the “Fire, Water, Burn” chorus. Or, if you went to college in the late 90s like me, you probably know it by heart.

About the Author

I write non-fiction, fiction, and run the YouTube Channel The Girl in the Tiara. My first non-fiction book, The Hunt for Anna Pavlovna’s Stolen Jewels, will be published by Pen and Sword History in 2026. To keep in touch, sign up for my royal history newsletter here.