Share this Post

John Steinbeck traveled to the Soviet Union not once, but twice. Did you guys know that?

I found a reference to it while researching ballerina Maya Plisetskaya for The Dante Deception. A single sentence in one of the articles about her mentioned meeting Steinbeck in Moscow, and I did a double take.

I don’t know much about Steinbeck, but being born and raised in Salinas, you absorb quite a few details about his life and work. (Check out my East of Eden posts here.) His trips to the Soviet Union had somehow fallen under the radar entirely. I had to know more.

Just Below Acrobats

Published in 1948, A Russian Journal (affiliate link) by John Steinbeck is his travelogue of a trip taken the year before – more about sights, sounds, and food than politics or polemicism. Steinbeck traveled with the famous wartime photographer Frank Capa, and my paperback included black-and-white prints of Capa’s photos. The two of them went to observe and report on the everyday life of post-war Russia. In addition to Moscow, they visited Ukraine, Georgia, and the city of Stalingrad. This book is a 200-page record of their experience.

The closest comparison for this book I can think of is to Anthony Bourdain’s travel show, Parts Unknown. In each episode, Bourdain meets up with a fixer, native son, or English-speaking local luminary. Together, they proceed to eat, get hammered, and illuminate some historical or cultural point you might not otherwise learn. Steinbeck and Capa share a dry wit that reminds me of Bourdain’s. They play practical jokes on each other. They insult each other. They torment each other. They’re engaged in travel not for the hell of it, but with a specific creative purpose in mind.

Here’s what surprised me: in parts, this book is laugh-out-loud funny. These guys are hilarious.

Their contact at Voks, the cultural relations bureau, asks Steinbeck what new writers are coming up in America. Steinbeck isn’t sure. He says that the people who should have been practicing their craft just spent four years fighting a war instead (as if the Soviet writers haven’t?).

This response really confuses the Voks guy. He can’t figure out why it’s so hard for Steinbeck to describe the literary scene in the U.S. Why don’t American writers get together and create associations? he asks. Stalin, he tells Steinbeck, says that “writers are the architects of the human soul.”

And here’s Steinbeck’s response: “We explained to him that writers in America have quite a different standing, that they are considered just below acrobats and just above seals.”

Even the hubby laughed at that one.

“We explained to him that writers in America have quite a different standing, that they are considered just below acrobats and just above seals.”

A Russian Journal by John Steinbeck

Eat, Drink, and Be Wary

Food is a key part of any culture – tasty grub transcends language barriers. Hospitality is often indicative of attitudes toward foreigners, as well as more obvious stuff like economic conditions.

Steinbeck spends quite a bit of time on food. “We had just about begun to believe that Russia’s secret weapon, toward guests at least, is food,” he writes. Expect to drool over some of the meals, from the shashlik (barbecued meat kebabs) to the cold boiled Georgian chicken with green sauce, spices, and sour cream to the fried cakes full of sour cherries topped with honey.

There’s one meal you might not drool over, though.

It’s the hearty breakfast served by Mamuchka, whom Steinbeck called “the hardest-working woman I have ever seen.” A farmer’s wife in Shevchenko, Ukraine, Mamuchka cooked morning, noon, and night to make sure Steinbeck and Capa never went hungry. After a late dinner at 2:30 a.m., Capa and Steinbeck awoke the next morning to the following:

The breakfast must be set down in detail because there has never been anything like it in the world. First came a water glass of vodka, then, for each person, four fried eggs, two huge fried fish, and three glasses of milk; then a dish of pickles, and a glass of homemade cherry wine, and black bread and butter; and then a full cup of honey, and two more glasses of milk, and we finished with another glass of vodka.

I know what you’re thinking: holy shit, how much vodka was that?

Maybe this vodka isn’t as high a proof as we think. Maybe the family burned it off by doing hard labor in the wheat fields immediately after consuming it. Or maybe they’re just world-class drinkers. I’m a little in awe, either way.

War, War, What Is It Good For?

You just can’t escape the after-effects of war in this book. So many of the roads are pitted with shell holes. So many of the homes in Ukraine have been burnt. Mamuchka’s only son had been killed. She only said one thing about him – “Graduated in bio-chemistry in 1940, mobilized in 1941, killed in 1941.” Stalingrad was in such pitiful shape that three years later, they were still working on tearing it down. They haven’t even begun to rebuild it yet.

One couple in Ukraine was only beginning to rebuild their house. Steinbeck and Capa saw them in the village of Shevchenko I (not to be confused with Mamucha’s village, also called Shevchenko and labeled “II”). On the way into the village, Steinbeck notes that all the pine trees are torn up with machine-gun fire. There are burned-out tanks and trucks littering the roads.

When they get to Shevchenko, they learn that before the war, there were 362 houses. After the Germans went through, there were 8.

Now that the residents have returned, they’re working hard to rebuild. While meeting with the town council to talk about agriculture, Steinbeck looks across the road and sees a couple working in the rain, struggling to lift heavy beams for a roof frame. Since 1941, when their house was burned, they and their three children had been sleeping in holes in the ground. A townsman points them out and tells Steinbeck, “There cannot be anyone in the world so wicked as to want to put them back in holes under the ground.” Hint, hint. (There’s an underlying fear in the Soviet Union during this time that America wants war.)

Stalingrad was worse.

Their hotel room looked out on “acres of rubble.” But the rubble wasn’t deserted, even though it was full of weeds. People lived in it because there was nowhere else to go. When their buildings were bombed out, people moved down into the basements and cellars, now buried under rubble. Steinbeck describes a young woman emerging from the rubble to go to work, combing her hair as she emerges. Steinbeck is amazed by her clean clothes and proud, feminine appearance. I’m amazed, too.

Another young woman wasn’t so lucky. She lived in a hole next to a garbage pile behind the Intourist hotel. Here’s how Steinbeck described her:

“She had long legs and bare feet, and her arms were thin and stringy, and her hair was matted and filthy. She was covered with years of dirt, so that she looked very brown. And when she raised her face, it was one of the most beautiful faces we have ever seen. Her eyes were crafty, like the eyes of a fox, but they were not human….Somewhere in the terror of the fighting in the city, something had snapped.”

This girl climbed up out of her hole, rummaged through the garbage heap for something to eat, and dozed in the weeds. One morning, Steinbeck saw another woman give her some bread. She wouldn’t eat until the other woman had gone. Then she tore into the bread like an animal. When her shawl slipped off her shoulder, she pulled it back up and “patted it in place with a heart-breaking feminine gesture.”

What was the thing, the moment, that broke her?

What would have happened to us in her place? The Soviet censors didn’t confiscate many of Capa’s photos, but they kept every photo he had of this girl. I wish I could have seen what she looked like.

A Few Random Observations

- So, you guys remember Jaws from those 1970s Roger Moore Bond movies? In the first chapter of the book, Steinbeck mentions two Russians with stainless steel grills – a male pilot and a female stevedore. I didn’t know what a stevedore was, either, so don’t feel bad.

- A beekeeper in Shevchenko I had just gotten six new queen bees from California. They were supposed to be more resistant to frost and he was freaking thrilled. You have to appreciate the little things.

- Steinbeck and Capa’s driver in Stalingrad was a car guy. I know the breed because I married one. The only words of English he knew were the cars he loved: ” ‘Buick,’ he would say, ‘Cadillac, Lincoln, Pontiac, Studebaker,’ and he would sigh deeply.”

- A week or two into the trip, Steinbeck misses seeing women with nail polish, mascara, and lipstick. I polished my nails and toenails after I finished the book just because I can. And because I’m trying harder to appreciate the little things.

A Russian Journal isn’t a treatise or a Pulitzer-winning piece of investigative reporting. It’s a simple travelogue, and that’s all it’s meant to be. Like any traveler, Steinbeck has his moments of awe and the moments when he’d clearly rather be anywhere else. By page 208, he says, “By this time I had reached a point where I could not drink vodka at all.” But the whole thing is a fascinating glimpse into the sights and sounds of the post-war Soviet Union. If you’re into Steinbeck or Russian culture or history, it’s well worth your time.

About the Author

I write non-fiction, fiction, and run the YouTube Channel The Girl in the Tiara. My first non-fiction book, The Hunt for Anna Pavlovna’s Stolen Jewels, will be published by Pen and Sword History in 2026. To keep in touch, sign up for my royal history newsletter here.

Image Credits

Header image: RIA Novosti archive image #493933, Anatoliy Garanin, CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

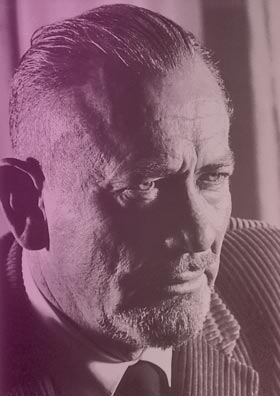

Steinbeck: John Steinbeck 1962 by the Nobel Foundation, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Stalingrad: Pavlov’s House, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Affiliate Links

I’m a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. The links in this post to A Russian Journal by John Steinbeck are my Amazon affiliate links. If you choose to buy the book through this link, I’ll earn a few extra cents.

Tell the World