Share this Post

Last Saturday, I went down to the track in my yard (I live in the country) and ran a few miles. When I run, I almost always think about writing.

Some days it’s marketing, sometimes it’s plot points I need to hash out, others it’s character development or motivation. If I’m too deep in thought, sometimes I’ll take a header on this stupid rock on the northeast curve of the track. Note to self: dig that sucker out.

Anyhoo, since I finished the first draft of The Dante Deception, the revision process has been on my mind. I still can’t explain why this happened, but all of a sudden, I realized the entire process of writing, editing, and producing a book is like The Princess Bride.

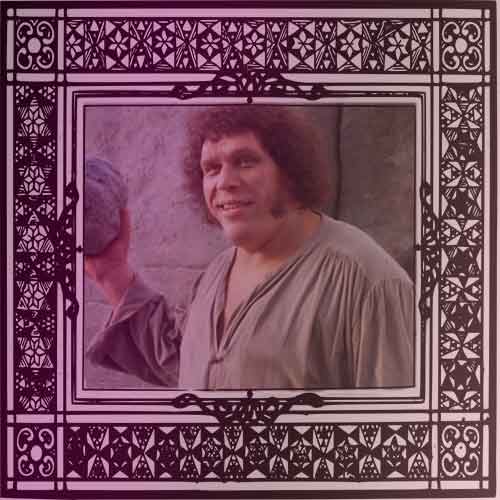

Fezzik: The Rough Draft

When I’m writing my first draft, I’m Fezzik. All power and no grace. A brute-force solution to the problem that is the blank page. Awful sentences? Fezzik doesn’t care. Fezzik bangs them out and moves on because the page is no longer blank – the problem has been solved. He has enough refinement to know that just typing “aaa aaa aaaabbb” is not writing. He knows there need to be real words, about the story, in some logical progression. And he can put ’em down. And then he’s happy.

Example #1: Remember when Fezzik and Inigo are storming the castle and they need to get the gate key away from the gatekeeper? “Fezzik,” Inigo says, “tear his arms off.” This is a solution Fezzik is okay with because it achieves the goal. He steps forward to do it, and the gatekeeper says, “Oh, you mean this gate key.” You are Fezzik. The blank page is the gatekeeper.

Example #2: Remember when Inigo is smashing himself against a locked door that Count Rugen has already fled through? Inigo shouts for Fezzik as he smacks himself against the door, over and over again with no effect. Inigo is not the right man for this job. Fezzik is. Fezzik smacks that door open and Inigo can move on. Was it elegant? Nope – a lockpick would have been more elegant. Was it peaceful? Nope – that door is busted right off its hinges now. But Fezzik got the job done. You are Fezzik. The blank page is the door.

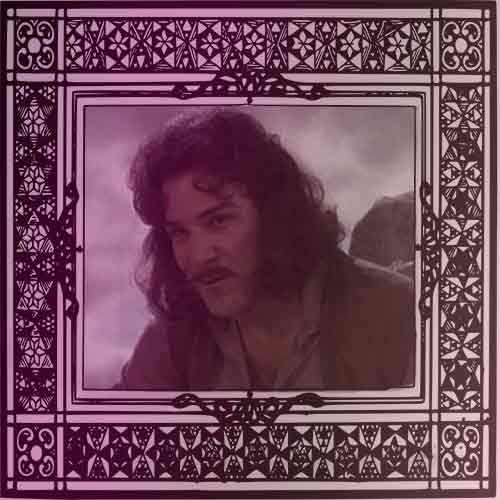

Inigo: The Second Draft

The page is no longer blank. Brute force won’t help you turn the plodding words left behind into a work of art. Now, you need to be Inigo. Inigo knows one thing and he knows it well: swordplay. He knows the thrusts and feints and what terrain they work on. He’s so knowledgeable, in fact, that he can identify these moves when used against him – with either hand. He is concerned with matters of skill, yes, but also timing and flair and fairness.

You need to thrust and feint and parry with your settings, characters, plot, and language the way Inigo fights with a sword. You’re looking not only for speed, but for grace. Not only for victory, but a fair win. Not only for competence, but elegance. And when there’s something he wants, he never gives up. Because you might be Inigo for one draft, two, three, four, or (if you’re me), eight or nine drafts.

Example #1: Remember when Inigo’s sword gets flipped away from him during the battle with the Man in Black? It landed in a clump of grass beneath the rock ledge where he was standing. He jumped, did a giant swing on a disintegrating rope between two crumbling walls, nailed the dismount, and landed within arm’s reach of his sword. If your story feels out of control, find the most elegant way to regain control. It might take you a chapter out of your way (the giant swing) and you might need to add a minor conflict (the dismount), but if you stick the landing (bridge the awkward plot gap by showing off a character’s skills or development), the judges (even the French one) will reward you.

Example #2: Remember when Inigo gets stabbed by Count Rugen and almost gives up? Almost. And then he says what is surely the godfather of Arya’s Prayer: “Hello. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.” And it snapped him back to life. When you get lost in the woods of editing and you think all the threads of your story are bleeding out of you as if Count Rugen stuck you himself, bring yourself back to your center. “This is a story about Hero. He wants X, but Y does Z. He will do A until he is within reach of X.” And ask yourself how the part you’re working on supports your mantra.

Note: Remember when Inigo pretends to be left-handed so the battle with the Man in Black lasts longer? Don’t do that.

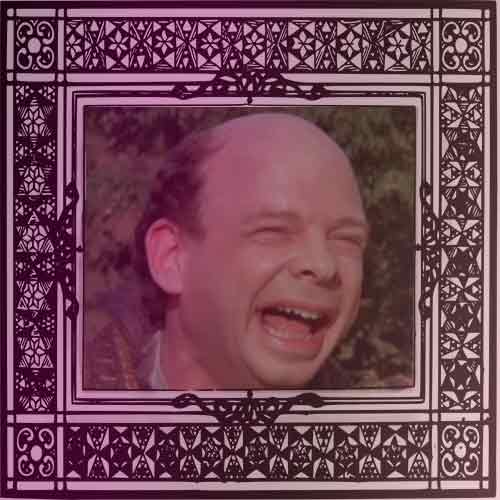

Vizzini: The Third Draft

Okay, your prose is looking pretty tight. The sentences have some zing, things move at a pretty good clip, and the characters and plot develop like film. Now, you pretend you’re a small bald man with the knowledge and foresight to start a war. Why? Because it’s time to poke every hole possible in your story and you better make sure it (and you) survive.

Vizzini plays all the scenarios in his head before making a decision. Gonna make a run for the Cliffs of Insanity with a kidnapped woman? Better know how fast it takes to get to the cliffs from Florin – and that you’ll be going through eel-infested waters.

Realize your brain is strong, but your weaknesses lie in strength and agility? Hire help to get past those obstacles.

In other words, Vizzini does the math. So now you have to do it, too. Question every action, every plot device, every simple statement of fact you make. Don’t have your hero taking off from Australia at night and landing in Moscow three hours earlier. These are small details, but they’ll trip you up. If there’s anything you glossed over or figured “no one will notice,” now is the time to sack up and fix it.

Would it be more helpful to be Vizzini before you’re Inigo? Perhaps. But remember all that twirling and swirling you did as Inigo? The story changed in lots of little ways as you parried your way through it. If you were Vizzini before, you’d still have to be Vizzini again now to make sure Inigo didn’t write a check you (Vizzini) can’t cash. This is best done after your manuscript sits, unlooked at, for at least two weeks. No exceptions.

Example #1: Remember when Vizzini sticks the torn uniform of a soldier from Guilder onto Buttercup’s saddle after he kidnaps her? He planted a clue – and you need to trace the clues in your story to see if they fall into place. Every story has clues, no matter the genre: how the hero feels about the heroine, why that planet is abandoned, etc.

Note: Remember when Vizzini says “inconceivable” after everything that sucks? Don’t do that. If you have a word or phrase you overuse (especially in the narration), do a “find” and swap out 80% of the usages.

Buttercup: The Book Cover

Now, your text is as perfect as it’s realistically gonna get. But the text isn’t what people are going to see first. That distinction belongs to your cover. This is when you need Buttercup. Just look at her face – you know what she’s thinking and feeling without her needing to say a word. Your book cover needs to convey what it’s about and some sort of mood or tone without the blurb, sample, or your lovely writing. It needs to wear its heart on its sleeve. NO tricks. No romance-novel clinching couple if your book doesn’t deliver on the basic premise of a romance novel: a happy ending.

Example #1: Remember when she’s just married the prince, and the old king and queen walk her to her room? She gives the old king a kiss and he asks her what for. She says it’s because he was always kind to her and because she plans on killing herself once they get to the honeymoon suite. No artifice, no lies, nothing but the brutal truth, even when she’s wearing the prettiest dresses. Never attempt to deceive a reader with your book cover. That includes putting an awful cover on your book that makes the reader think your book is awful. If your book isn’t awful, don’t deceive the reader by putting an awful cover on it.

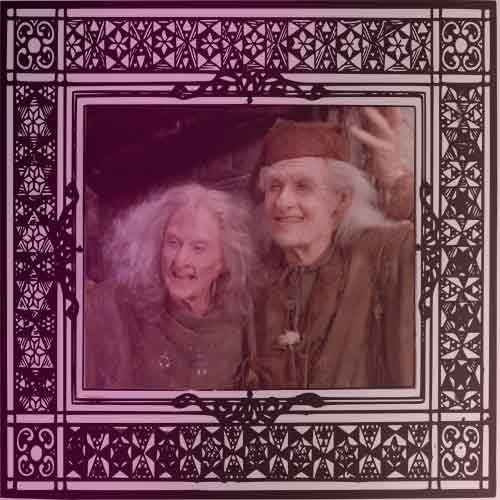

Miracle Max: The Marketing Strategy

Miracle Max is grumpy. Miracle Max is lazy. Miracle Max got fired by the king’s stinking son and doesn’t want to talk about it. Guess what? When it comes to marketing our work, we’re all Miracle Max.

As for me, I’ll look for any excuse not to do it. It’s hard. It’s scary. Every failure affects my confidence. So does the fact that I don’t know what I’m doing. I really don’t want to be bothered, noble cause or not.

But then a voice starts telling me that I’m betraying true love by not helping Inigo and the Man in Black. Okay, so it’s more like my conscience telling me that no good things can happen unless I try and put my work out there. But the idea is the same. Get up, do it, and if you fall (or get pushed), pick yourself up and try again.

Example #1: Remember when Miracle Max differentiates between mostly dead and dead? Sometimes marketing is going to feel like splitting hairs, as you try to justify spending money on BookBub versus Facebook ads versus AdWords versus eReaderNewsToday. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try.

Example #2: Remember when Miracle Max and Valerie wave to the guys as they leave? Valerie asks if Max thinks the plan will work. Max says it would take a miracle. He’s a skeptic. You need to be a skeptic when it comes to all the grandiose marketing schemes on the market today. So many self-published authors are making money by selling things to other self-published authors. Systems, courses, software – stuff that they promise will jump-start your sales. I’m deeply skeptical of the salesmen who started out as fiction authors. If their books made so much money, why not just keep writing them and making more money? Why does it seem like a better idea to get me to buy something so I could have their level of success? Is that level of success really that successful if they still need to pitch me? All I hear is Max and Valerie: “Think it’ll work?” “It would take a miracle.”

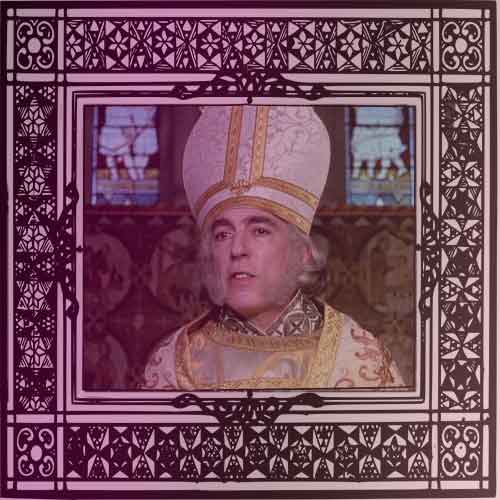

The Clergyman: Reviewers

Maw-wage. Twu wuv. A bwessed awangement. Sometimes you can’t understand what the hell this guy is saying. You only have context to go on. It’s gonna be that way with reviewers, too. Some will give your book five stars – yay! But some will give it two stars because they just didn’t like the character. And you’re thinking, what the hell does that even mean? Why not? What about a hero on a quest don’t you like? Sometimes, you’ll have context to help you out. Others, you won’t. And sometimes, you’ll just have to smile and nod and wait for them to finish talking.

But, much like the clergyman is necessary to officiate a marriage, reviewers are necessary to help get the word out about your book. You are not allowed to interrupt them, silence them, hurry them, or (in my opinion) even respond to them. You gave your book to them. Thus ended your participation. The clergyman doesn’t show up at your house and tell you and your spouse how to make up after a fight. He doesn’t show up to wish you a happy birthday. You came to him for a specific task, which he performed. And then both sides went their separate ways.

Note: Never put words into a reviewer’s mouth the way Prince Humperdinck bullies the clergyman into pronouncing him married to Buttercup. You saw how that ended for Humperdinck.

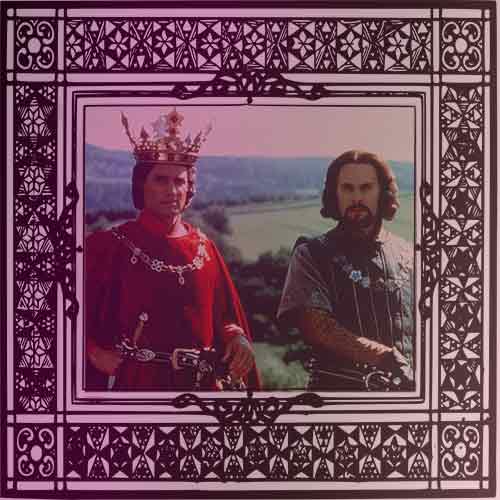

Prince Humperdinck & Count Rugen: Trolls

The arrogant tilt of the chin. The eyes looking supercilliously down the nose. This is a person who believes they are smarter and better than you are. They may even believe they are doing the right thing by telling you they are smarter and better than you are. They are not. They are Prince Humperdinck. They are warthog-faced buffons. Much like Westley, you must let them live. Unlike Westley, you must not challenge them to a duel to the pain.

But who’s that standing behind Humperdinck? Pale skin, beady eyes, and a cold, cruel stare? It’s a different kind of troll. This troll isn’t so much interested in himself as he is in picking a fight for the sake of picking a fight. He has no personal stake in arguing with you, unlike Humperdinck. He just likes arguing. He types in a nasty comment, knows it will set you off, and then goes and calls some more people bad words on YouTube. Maybe he’ll check back. Maybe he won’t. But every moment you spend obsessing about his comment is one moment of life sucked away by the virtual version of Count Rugen’s machine.

Example #1: Remember when Humperdinck and Rugen are in the Pit of Despair and Humperdinck tells Rugen that he hired Vizzini to kill Buttercup? What a dick, right? Trolls have an agenda you can’t see and you can’t know. Ignoring them is the only solution. You will not change their minds. You will not convince them of the merit of your book. You will only give them more material to work with.

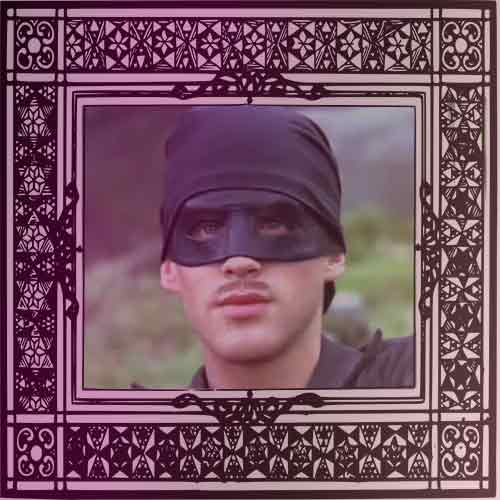

Westley AKA The Man in Black: You

Westley is just a humble farm boy whose dedication to Buttercup kept the Dread Pirate Roberts from killing him. He braved the Fire Swamp and was only mostly killed by The Machine. Without the use of his legs, he used his wits, his voice, and his hands to battle the villain – everything he had available to him. He beat Vizzini by building up an immunity to iocane powder, for the love of Pete.

Like Westley, we need to be the architects and the heroes of our own stories.

Except it’s not a story – it’s our lives. We need to understand how to market ourselves. Westley did – he saw the genius in the way the Dread Pirate Roberts brand name transcended the individual. We need to work through pain and death. We need to have faith when everything we want seems to have been taken from us. Because you know what the torture and the beauty and genius of being a writer is?

Death cannot stop us. It can only slow us down.

About the Author

I write non-fiction, fiction, and run the YouTube Channel The Girl in the Tiara. My first non-fiction book, The Hunt for Anna Pavlovna’s Stolen Jewels, will be published by Pen and Sword History in 2026. To keep in touch, sign up for my royal history newsletter here.

Share this Post